“Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes?” by John Adams is a contemporary piano concerto that has quickly become one of my favourite compositions of all time. The name comes straight from a 1950s interview with Dorothy Day, the Catholic social activist, who quoted Martin Luther’s famously cynical remark. Adams himself says the phrase was taken from Luther, and he’s used it to frame a work that feels, in every sense, a modern “Totentanz” – a dance with the devil.

The American Totentanz – funky, bright, and unapologetically bright

If you’ve ever played or listened to Liszt’s Totentanz, you know its dark, plague‑laden mood. Adams, by contrast, writes an “edgy piece with a diabolical soul” that is more funk‑laden and lively. While Liszt’s work was born out of despair, drawing on the Black Death and 1948 uprisings in Europe, Adams’s concerto was commissioned by the Los Angeles Philharmonic. He admits that the inspiration came from Liszt’s Totentanz, but the result is “American” – a jazz‑laden, rock‑infused take that sounds more like a city street than a medieval graveyard.

A piano part that asks you to dance

The concerto opens with a powerful piano arpeggio that cuts through a thick orchestral backdrop. Adams explains that he was inspired by jazz, funk and, more generally, American music, but that doesn’t erase the romantic or classical lineage that runs through his work. Stravinsky, Liszt, Shostakovich and even Sergei Prokofiev are all audible in the piece, each contributing a piece of the puzzle that makes the concerto feel fresh yet familiar.

The piano writing is “technically fearsome,” as Musical America described, and it is a true showpiece for pianist Yuja Wang, who premiered the work with the Los Angeles Philharmonic under the baton of Gustavo Dudamel. The part demands not only virtuosity but a sense of mischievous fun, something that’s missing from most contemporary concertos.

Three movements in one breath

Adams’s concerto is in three movements, played without pause:

| Movement | Marking | What it feels like |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gritty, funky, but in strict tempo | A punchy opening that immediately grabs your attention. |

| 2 | Much slower; gently, relaxed | A lyrical, almost nocturne‑like interlude that’s surprisingly lively. |

| 3 | Più mosso: Obsession / swing | The crescendo, where the piano’s “obsession / swing” motif explodes into a full‑blown orchestral roar. |

The whole piece lasts about 28 minutes, a compact span that feels both cinematic and intimate.

The second movement, a “breathing point” that refuses to be a lull

When critics say the second movement is a “breathing point,” they’re right, but it’s not the soft, relaxing music you might expect. Instead, it’s a dark, shadowy interlude where bass provides a low‑end foundation, strings glide legato, and the piano weaves a shimmering web of melodic threads above. As the San Francisco Classical Voice notes, the “nocturne idyll is broken… and the concerto takes off in a final section of pure energy.”

The third movement, where the devil’s got a new swagger

This is where the concerto truly shines. The movement starts quietly on the piano, then builds to a full orchestral beast that feels like a “city piece” – all steel girders and glass monoliths, pounding factory rhythms, fatally seductive temptations around every corner. The rhythmic pattern, which Adams calls “Obsession / swing,” is both swinging and obsessed, making the finale a riot of syncopations, jazz‑inflected brass bursts, and ironic sampled honky‑tonk piano. It’s a “modern‑sounding” piece that still carries the soul of a late‑romantic work.

Why this piece matters

Adams’s lack of formal piano training, as he admits, actually pushed him to think differently. The concerto shows how a composer can weave together minimalist rhythmic cells, jazz motifs, and classical structures into a single, cohesive statement. The performers, Yuja Wang, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and Gustavo Dudamel, brought the work to life with a “highly rhythmic, technically fearsome” piano part that was both “excitably satisfying” and “boisterous.”

If the devil is up to his old tricks, he’s certainly doing it with a new groove. Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes? proves that good tunes can come from unexpected places, and that sometimes, the devil does bring a little funk to the dance.

#JohnAdams #MustTheDevilHaveAllTheGoodTunes #PianoConcerto #ContemporaryClassical #JazzInfluence #Funk #ModernMusic #YujaWang #LosAngelesPhilharmonic #GustavoDudamel #Totentanz #Prokofiev #Stravinsky #Liszt #Shostakovich #MusicReview #MusicCritique #ClassicalMusic #NewMusic #MusicMagazine #Orchestral #ContemporaryComposition #MusicInspiration

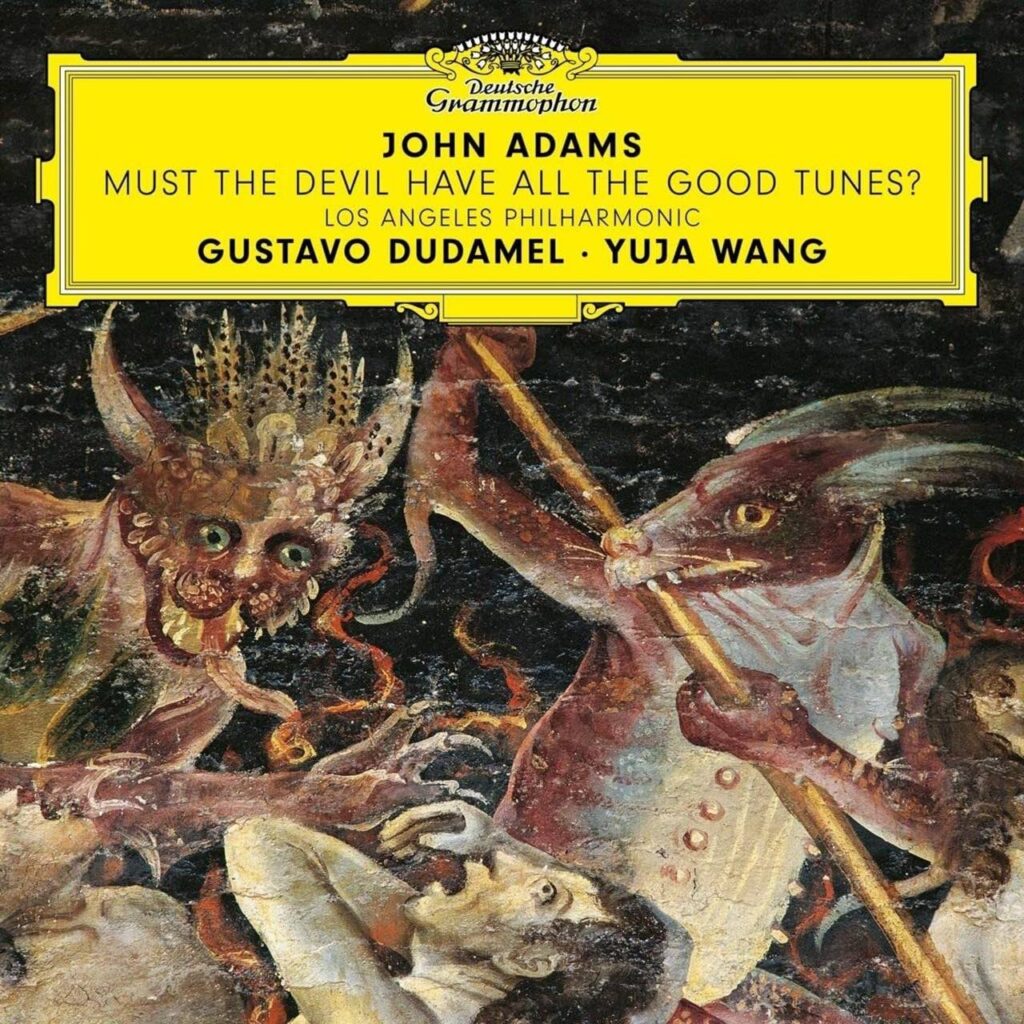

Photo artwork: © 2020 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Berlin