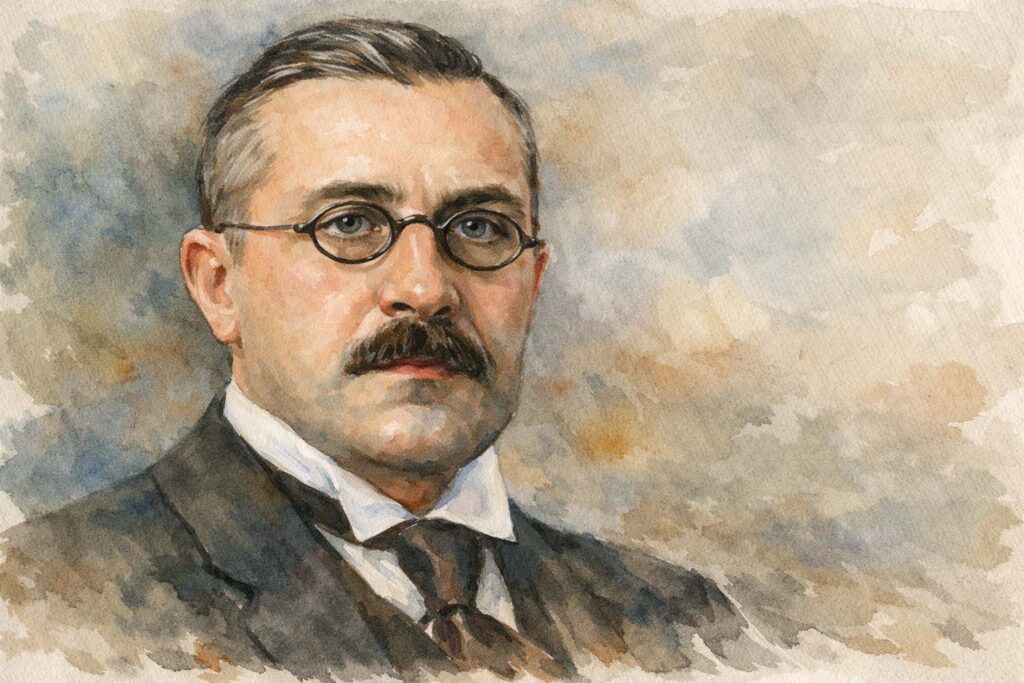

Max Bruch (born January 6, 1838, in Cologne, Germany — died October 2, 1920, in Berlin) was a German composer, conductor, and teacher whose music stands at the emotional heart of 19th-century Romanticism. Living through a period of radical musical change, Bruch remained steadfastly devoted to melody, clarity, and expressive warmth. Though history often reduces his name to a single iconic work, Max Bruch’s legacy is far richer, deeper, and more influential than popular memory sometimes allows.

Early Life and Musical Formation: A Prodigy Rooted in Tradition

Max Bruch was born into a cultured, musically supportive family. His mother was a singer and piano teacher, and his early musical education began at home. By the age of nine, Bruch was already composing, and at fourteen he completed his first symphony, an early sign of the disciplined craftsmanship that would define his career.

Bruch studied composition and theory with Ferdinand Hiller and Carl Reinecke, both respected figures firmly grounded in Classical and early Romantic traditions. These teachers shaped Bruch’s strong sense of form, counterpoint, and melodic balance. Unlike many later Romantic composers, Bruch never sought to overthrow tradition; instead, he aimed to refine and deepen it.

The musical world into which Bruch emerged was divided. On one side stood composers like Johannes Brahms, Mendelssohn, and Schumann, who believed in structural clarity and absolute music. On the other were Wagner and Liszt, championing music drama, chromatic expansion, and programmatic symphonism. Bruch positioned himself clearly in the former camp, often openly critical of Wagner’s aesthetics, an artistic stance that would both define and complicate his legacy.

Max Bruch and His Musical Language: Why He Matters

Max Bruch’s importance lies in his unwavering commitment to melody as moral force. At a time when music was becoming increasingly intellectualized or ideologically charged, Bruch believed deeply in music’s emotional immediacy. His works speak directly to the listener, prioritizing lyrical expression, balance, and human warmth.

Bruch was not an innovator in harmony or form, but he was a master craftsman. His orchestration is rich but never overloaded; his themes are memorable without being simplistic. This made his music immensely popular with audiences, even as critics and historians later accused him of conservatism.

Ironically, it is this very conservatism that has allowed Bruch’s music to age so gracefully. His works remain staples of the concert repertoire because they communicate without explanation. In this sense, some musicians have provocatively described Bruch as “an anti-modernist prophet”, a composer who proved that sincerity could outlast novelty.

Key Works by Max Bruch

Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 26 (1866)

This is Bruch’s most famous work and one of the most beloved violin concertos ever written. With its dramatic opening, soaring lyricism, and fiery finale, the concerto has become a rite of passage for violinists worldwide. Ironically, Bruch himself grew frustrated by its overwhelming popularity, once remarking that he wished it would finally “disappear.”

Scottish Fantasy for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 46

Inspired by Scottish folk melodies, this work blends national color with Romantic lyricism. It reveals Bruch’s deep interest in folk traditions—not as exotic ornament, but as emotionally authentic material.

Kol Nidrei, Op. 47

A profound work for cello and orchestra based on Jewish liturgical melodies. Kol Nidrei stands as one of the most emotionally resonant pieces in the cello repertoire and reflects Bruch’s deep respect for Jewish musical heritage, despite not being Jewish himself.

Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 51

Often overlooked, this symphony demonstrates Bruch’s command of large-scale orchestral form and his ability to sustain long lyrical arcs without reliance on theatrical effects.

Choral and Vocal Works

Bruch composed extensively for chorus, including oratorios and cantatas. These works were highly respected in his lifetime and reflect his belief in music as a communal and moral art form.

Who Max Bruch Influenced — and Who He Resisted

While Bruch did not found a “school” in the way Wagner or Liszt did, his influence was nonetheless significant. He served as a teacher and mentor to younger composers and worked as a conductor throughout Germany and beyond. His emphasis on craftsmanship and melody influenced generations of performers, particularly violinists and cellists.

Bruch’s aesthetic stance also provided an important counterbalance within Romantic music history. At a time when German music was becoming increasingly polarized, Bruch represented an alternative path—one rooted in tradition, clarity, and emotional directness. In this way, he indirectly influenced later composers who resisted modernism or sought to reconnect with tonality and lyricism.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Max Bruch

Max Bruch deserves to be remembered not as a composer of one concerto, but as a guardian of Romantic values at a moment of artistic upheaval. His music does not shout; it sings. It does not argue; it persuades. In an era obsessed with progress, Bruch believed in continuity, and history is slowly beginning to vindicate that belief.

To listen to Max Bruch today is to rediscover the power of melody, the dignity of form, and the enduring relevance of emotional truth.

Sources:

Encyclopaedia Britannica

Oxford Music Online

Classic FM

#MaxBruch #RomanticMusic #ViolinConcerto #ClassicalMusicHistory #RomanticEra #GermanComposers #OrchestralMusic #MusicLegacy #ComposerProfile